The BBC published an article about Chile yesterday: their “Reality Check” department came to the conclusion that while inequality is bad, poverty has declined, and wages have increased. The overall message seemed to be, “Things are improving! What’s the big deal?” Putting aside the tonal issues with the British Broadcasting Corporation crowning themselves arbiters for what makes protests in Chile legitimate or not, it’s also a tremendously unhelpful take, in that it doesn’t at all help to understand why the protests are happening. I’d instead wager that the metrics chosen by the BBC for their fact-checking are simply incomplete, and fail to capture the real economic grievance most protestors have—the high cost of living relative to income that Chileans face.

When a $1 metro fare is really expensive

A good place to start is with what started it all: subway fares. Mass transit in Chile’s capital of Santiago is provided by the Red Metropolitana de Movilidad (Metropolitan Mobility Network), formerly Transantiago. It is a kind of public-private hybrid that binds together no fewer than eight different private concessionaires that themselves are responsible for administering bus and train services.

Fares are at present approximately $1 USD. The fare is modified slightly depending upon the time of day, with fares during peak usage hours costing more than low usage hours. Fares are lower for buses, and greatly reduced fares are available for students and the elderly.

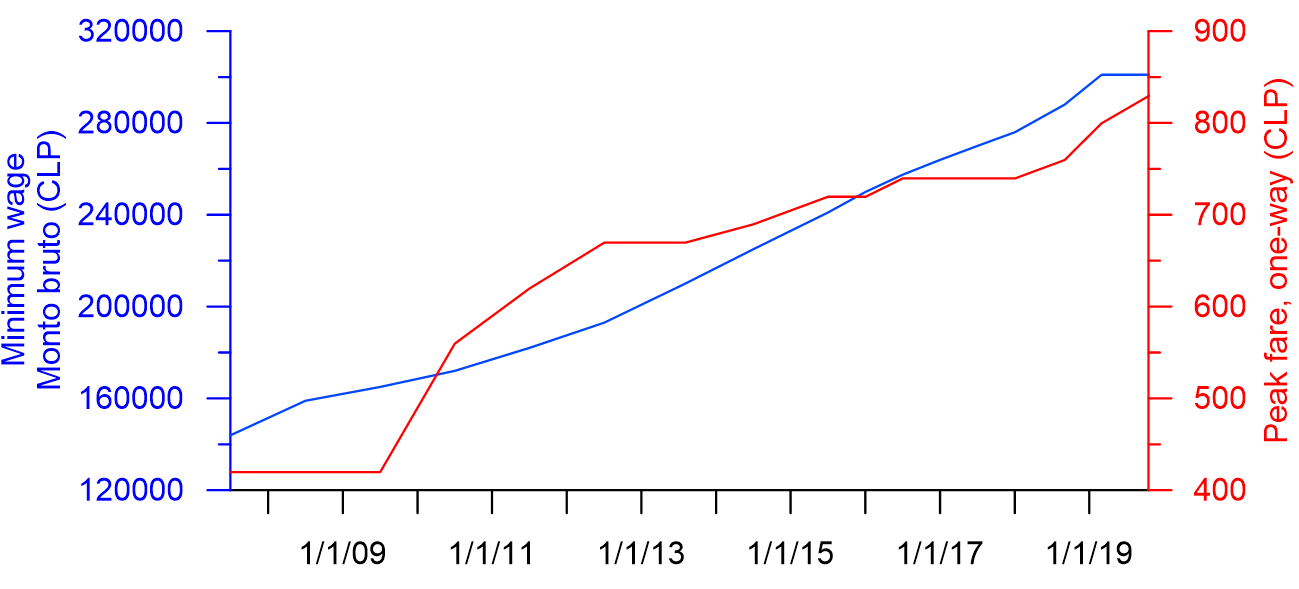

While the government partially subsidizes its operation, the Red Metropolitana is essentially run as a monopolistic business, and is designed to achieve a kind of financial self-sustainability through fare adjustments. The Red Metropolitana commisioned a panel of experts to calculate fare adjustments based on an indigestible formula (for the average person) that incorporates diesel prices, the exchange value of the American dollar, and market price for new tires, amongst other variables. One of the most influential variables is the Chilean consumer price index, and the dependence of fares on this has meant that fares have increased more or less in lock-step with inflation. Although peak fares have doubled since 2007, so has the minimum wage, so Metro fares have been essentially stable when evaluated as a proportion of minimum wage.

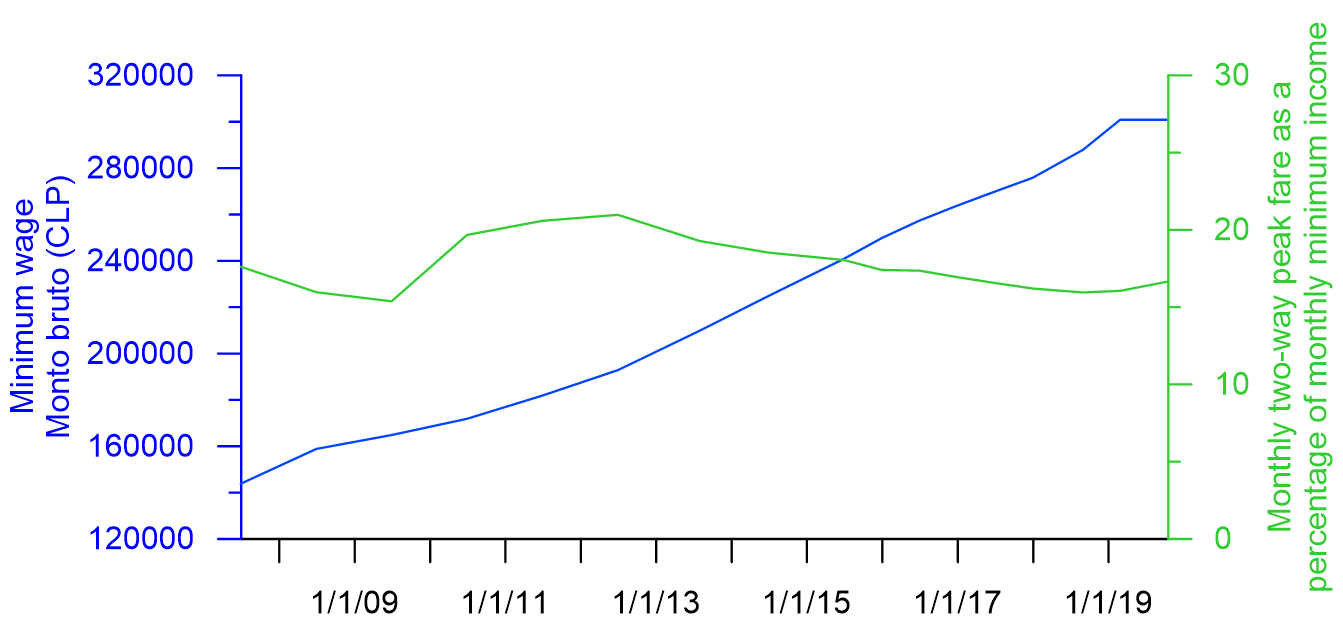

However, take note of the percentages at play here. Evaluated as a proportion of the historical minimum wage at the time of wage hikes, metro fees have accounted for between ~15% and 20% of an individual’s minimum wage income.

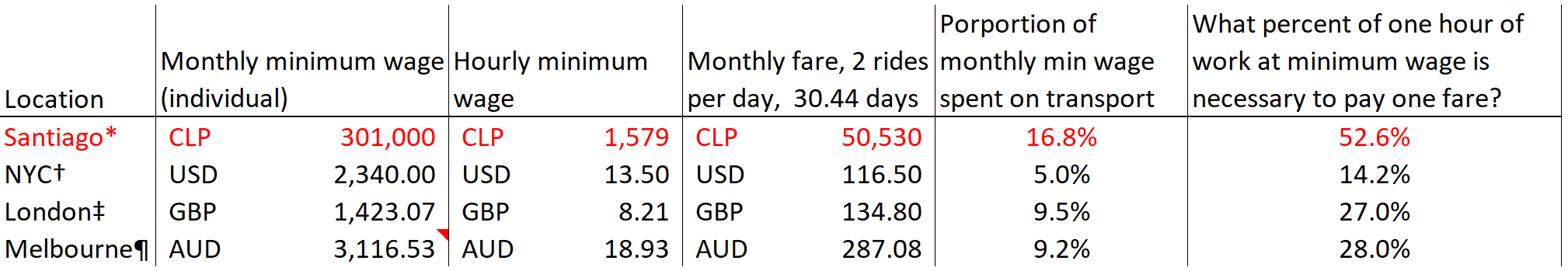

To put this number into context, let’s compare Santiago’s underground to the subway systems of New York, London, and Melbourne. First, I’ve put together some back-of-the-envelope calculations to show public transit fares as a proportion of minimum wage in these four cities. I use the now-retracted peak fare of CLP830 for the calculations of Santiago’s transit costs, but you can replace the cancelled peak fare with the active off-peak fare and the same general results still hold true.

Monthly and hourly minimum wage compared to transit fares for four cities.

* Hourly minimum calculated in base of a 44 hour work week over an average month of 30.44 days. Monthly fare calculated as 2 rides per day at peak hour over 30.44 days. Source: https://www.leychile.cl/Navegar?idNorma=1123300

† A minimum wage of $13.50 is applied to a 40 hour work week, which is the city minimum for small businesses; the minimum for large businesses is $15.00.

‡ I calculated the monthly minimum wage as the over-25 hourly minimum of £8.21 applied to a 40 hour work week, although UK law permits up to 48 hours of work per week. Monthly fare is taken from a monthly Travelcard for zones 1 and 2. Sources: https://www.gov.uk/national-minimum-wage-rates http://content.tfl.gov.uk/adult-fares-2019.pdf

¶ Calculated in base of a weekly minimum of A$719.20 per week for a 38-hour work week. Fare calculated as the price of a 365-day myKi pass for zones 1 and 2, paying only for 325 days, assuming two trips per day per month.

Therefore, as a proportion of minimum wage, Santiaguinos pay a significantly higher proportion of their wages in transit than in other cities in the “First World.” However, this simplistic analysis also fails to capture the entire picture, as Chile maintains a different, lower minimum wage for people older and younger than 18-65. Although these groups are eligible for reduced fare tickets, they are also often not part of the labor force, forcing the rest of the household to pick up these costs. Also, unlike cities such as New York City, there is no program of subsidized transit fares operated by employers for employees. The end result is that the poorest 20% of the country spends up to and in excess of 30% of their income on public transportation.

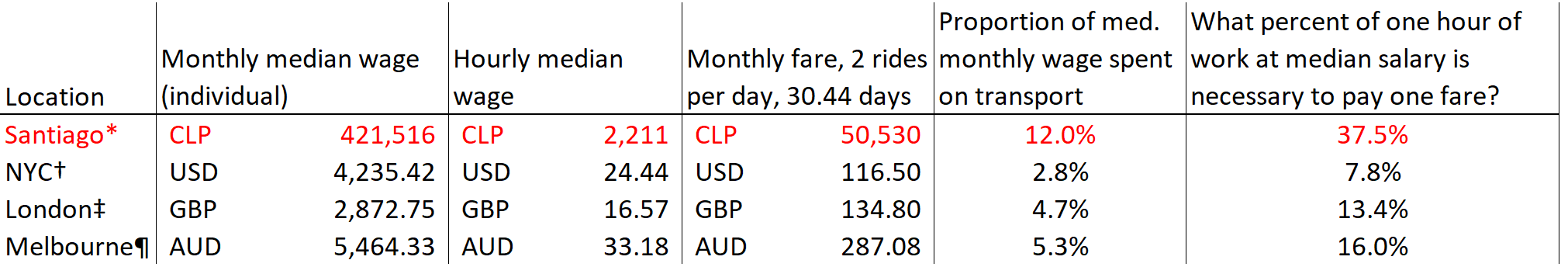

This is not good for the poorest demographic, but to truly grasp the scale of the problem it is necessary to consider averaged salaries. I look here at median salaries for these same cities, which are a more useful metric than mean salaries as in almost all nations the mean salary is grossly inflated by high-earning outliers.

*National data. Source: https://www.ine.cl/estadisticas/ingresos-y-gastos/esi.

† Source: https://smartasset.com/retirement/average-salary-in-nyc

‡ Source: https://www.cityam.com/where-can-you-earn-most-uk-pay-london-much-higher-any-other-part-uk/

¶ National data. Source: https://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/Lookup/6333.0Main+Features1August%202017?OpenDocument. Data for 2017 based on a weekly individual median salary of A$1261.

Keeping in mind that I have only the national median, and not the Santiago median, the first important point is that transit prices still comprise a significant part of a median wage earner’s monthly expenses. A median wage earner in Santiago pays more for mass transit, proportionally, than a minimum-wage earner in New York, London, or Melbourne.

Second, note that median salary in Chile is barely above minimum wage. This is in contrast to the other places listed, where median salaries almost double the minimum. Half of all working Chileans earn less than ~$575 per month, while 70% of working Chileans receive less than ~$750 per month; this is still less than the average monthly salary nationwide.

Everything else is proportionally expensive, too

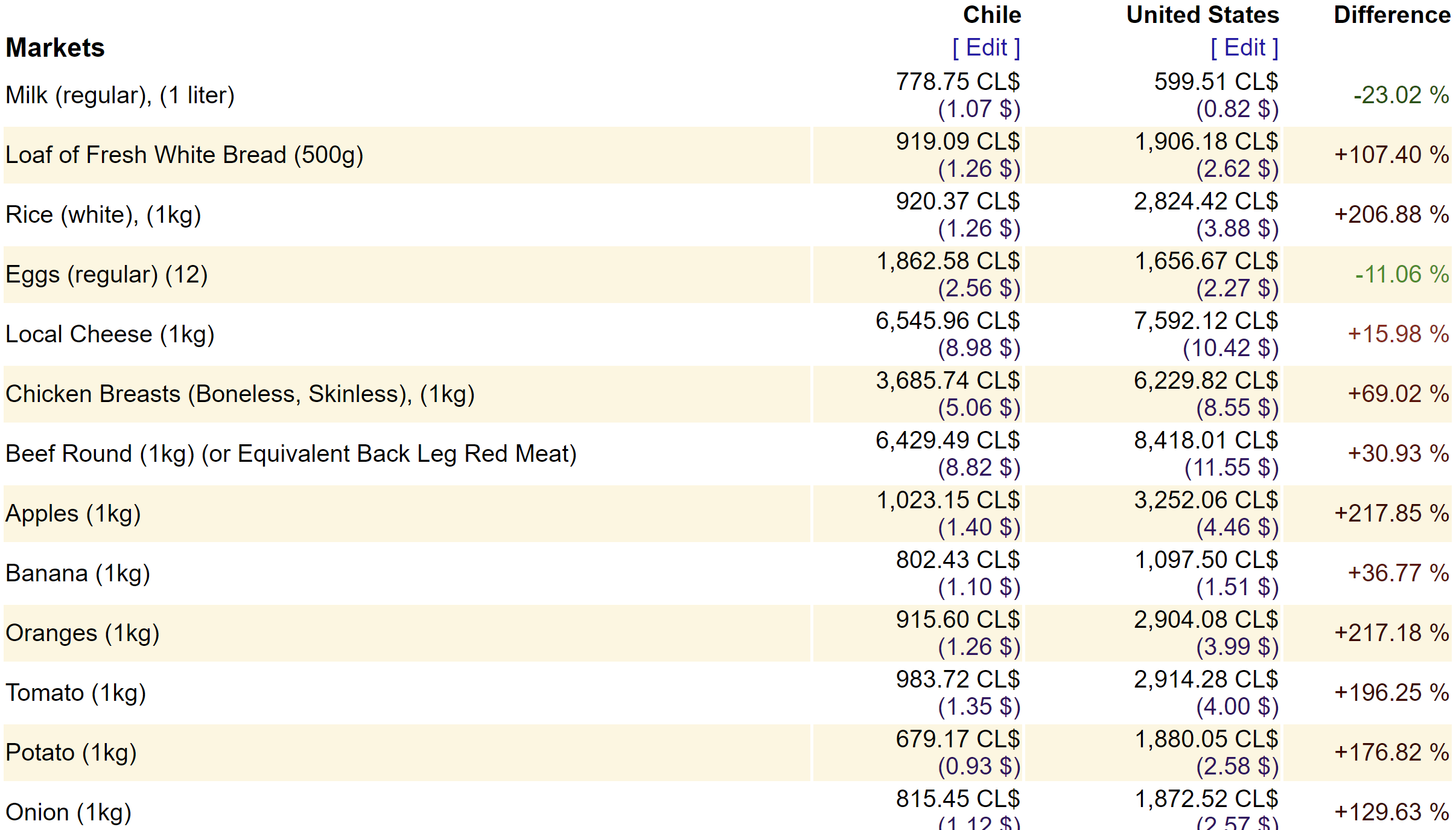

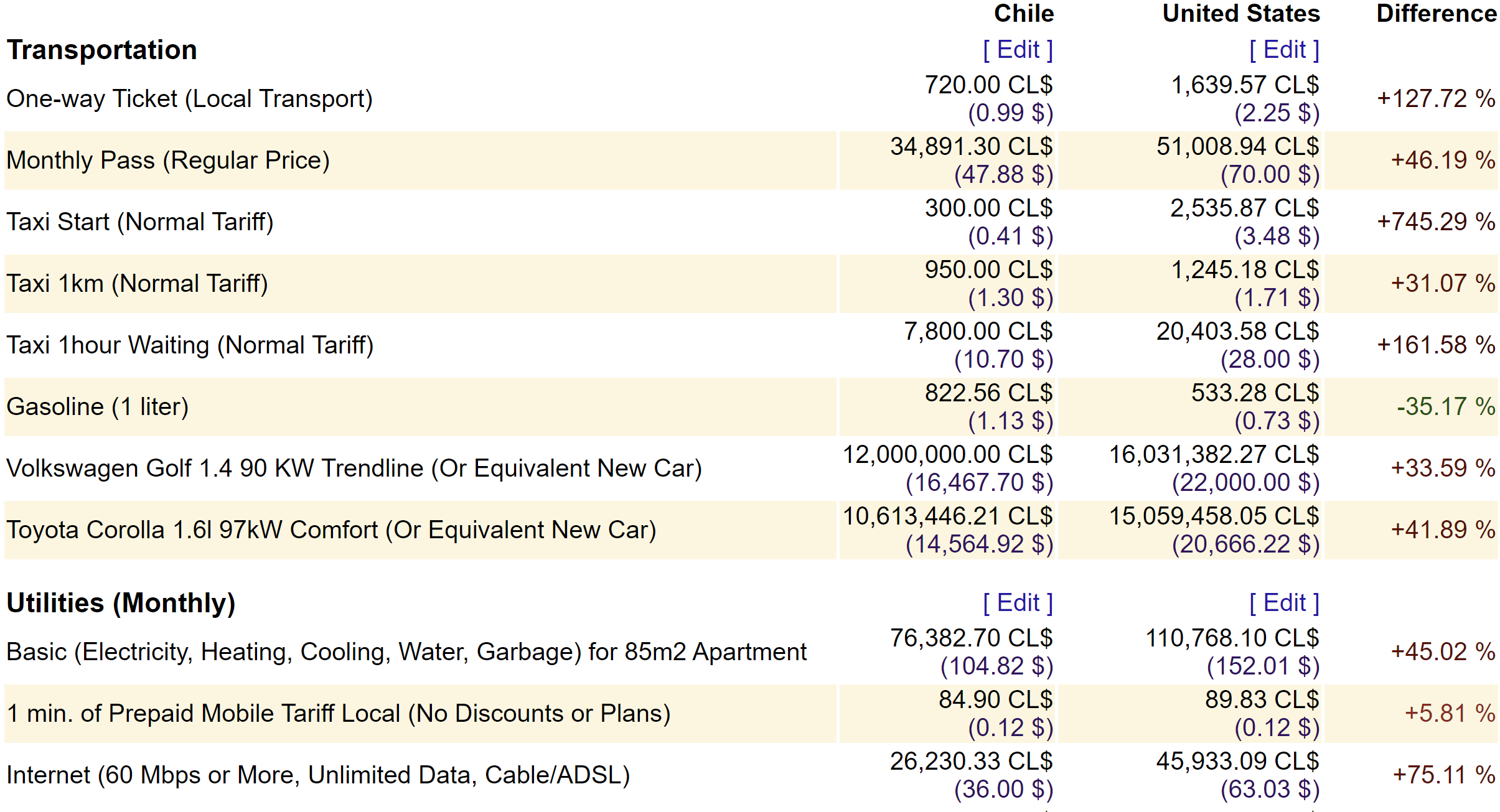

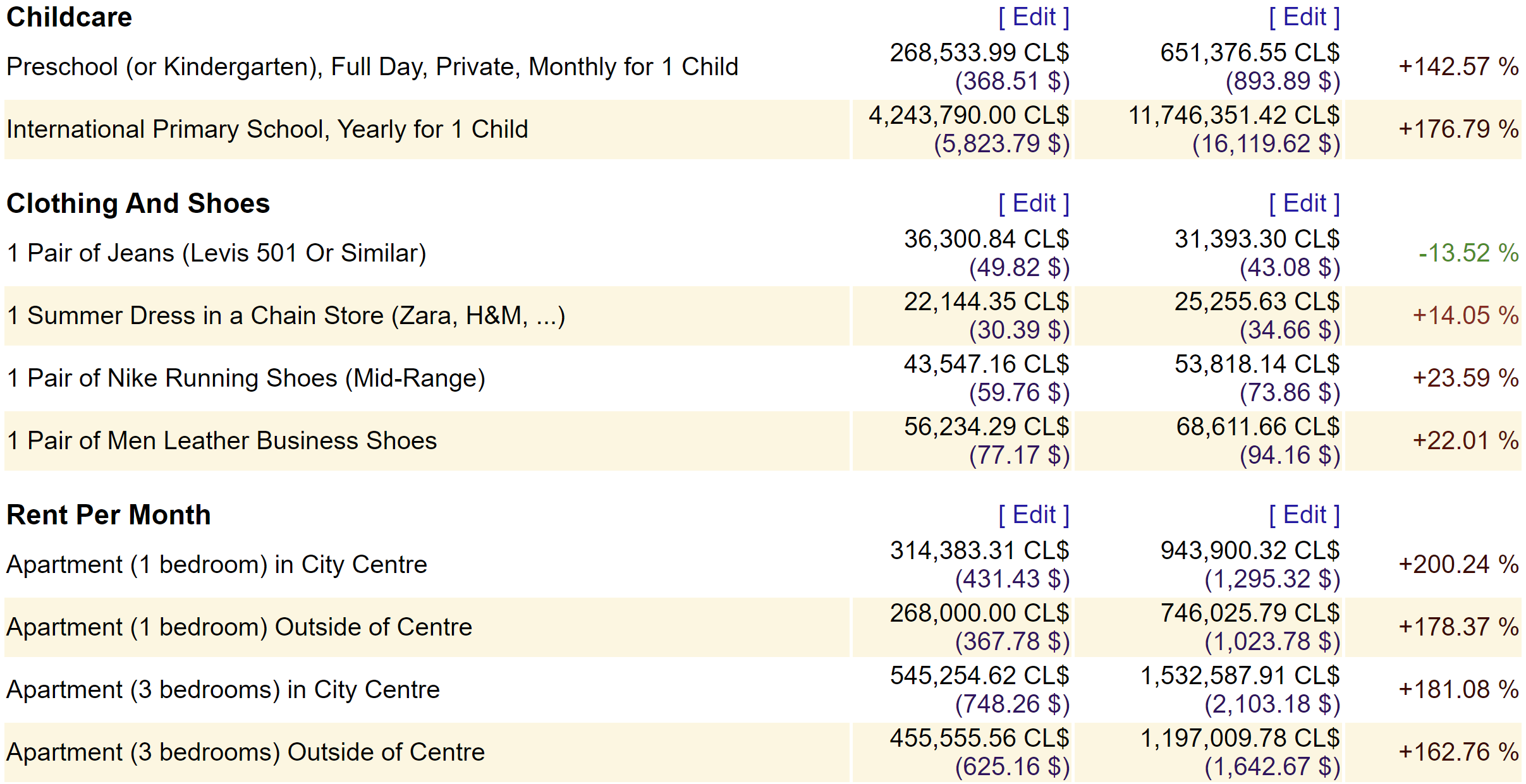

I’ve found it surprisingly difficult to quantify cost-of-living in Chile when compared to other countries, so if anyone reading has any advice I am all ears. The best example I could find is not the most robust, but illustrates a key point—goods and services are far more expensive in Chile when understood as a percentage of income.

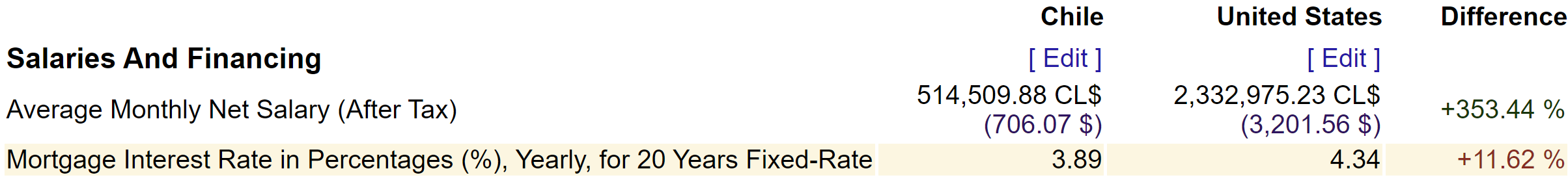

Numbeo is, from what I can tell, a type of crowdsourced cost-of-living index, where people can enter prices of goods and services in their home countries to compare them to others—therefore there’s inherently a bit of subjectivity involved. I compare below values of goods and services in Chile and the United States. According to contributors, averaged after-tax salary in Chile and the United States is ~USD$710 and ~USD$3200, respectively.

Chileans pay proportionally more for almost all goods and services than Americans (health care being a notable exception; not listed, and a much larger separate discussion). Of all indexes listed, the only index where Chile has an advantage is starting taxi fare. Several goods, such as milk and eggs, are more expensive in Chile in absolute terms, without even accounting for differences in income.

Chileans work longer hours, for less pay, to purchase essential goods and services that are proportionally more expensive than in the “First World.” For 30 years, since the return to democracy, people have grudgingly accepted the narrative that this is the price of development—that once the economy grows just a little bit more, finally the mere act of existing will start to become cheaper. People accepted the rosy picture that Piñera painted to the Financial Times literally the day before martial law was declared, in which he said this of Chile’s position in Latin America:

Chile looks like an oasis because we have stable democracy, the economy is growing, we are creating jobs, we are improving salaries and we are keeping macroeconomic balance

The question now on everyone’s mind is, if the economy continues to grow yet prices continue to grow with them…what is even the point of growing at all? What is prosperity, if I am paying the same portion of my salary for transportation as I was ten years ago? Or more pointedly, who is really benefitting from the current economic system, where the vast majority of the population pay more, and are paid less?

“It’s not for 30 pesos, it’s for 30 years,” say the thousands in the streets. Whether you agree with the sentiment or not, you ignore its roots at your own peril.

EDITED at 15:30 for grammar. I am going on very little sleep and i apologize for the errors.