When the classic British motorcycle marque Norton slumped into administration on Wednesday afternoon, the news was framed in the habitual way of a standard UK engineering corporate failure.

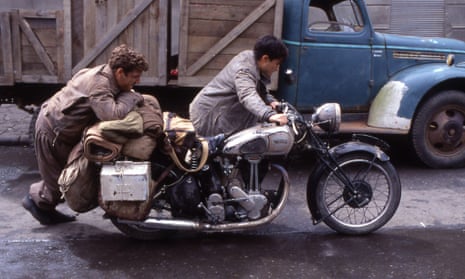

The 122-year-old brand – famed for roles in the Che Guevara memoir The Motorcycle Diaries and the James Bond film Spectre – had fallen victim to an assortment of overwhelming forces ranging from Brexit, a punchy HMRC pursuing the firm for £300,000 in unpaid taxes, and tough international competition that made it impossible for Norton’s traditional bespoke approach to succeed.

However, the story is far more complex than that. It is a pile-up that includes hundreds of hapless pension holders, together with unsuspecting Norton customers, staff and even government ministers, who repeatedly endorsed Norton as millions of pounds in taxpayer support flowed into the firm.

All will take a lot of persuading that this is merely a story of a plucky British company that is a victim of circumstance. Their anger looks likely to be directed principally towards one man: Norton’s boss, Stuart Garner.

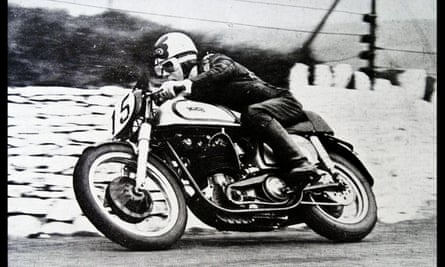

Garner bought the Norton brand in 2008, after it had been under US ownership and had ceased producing bikes. He pledged to return the marque to former glories that include a racing tradition dating back to winning in the first Isle of Man TT race.

Even before this week’s collapse, the businessman was being pursued by dozens of “ordinary working people”, some of the 228 savers whose pension pots added up to the £14m that was invested into Norton following a fraud.

Those savers had been persuaded by a conman to transfer their retirement funds out of conventional pension plans during 2012 and 2013. Their money was then locked up for five years into three new pension plans controlled by Garner – where the cash was invested in just one asset: Norton shares.

Garner has said he had no idea the funds had been raised fraudulently when he accepted them. He insists he too is a “victim” and that he thought he had longer than five years to pay the money back.

An investigation by the Guardian and ITV News has also found:

Dozens of pension holders are now accusing Garner of ignoring repeated requests to return their pension pots – years after the lock-in periods that prevented them from accessing their money have passed.

Millions of pounds in government-backed loans and ministerial endorsements were given to Norton, which enhanced the credibility of the firm and its owner.

Lengthy delays in promised deliveries of Norton motorcycles – which can cost as much as £44,000 each – despite customers saying they had paid deposits and sometimes even the full purchase price.

A £1m loan received by the motorcycle firm in 2008, that came directly from the proceeds of a tax fraud, for which two longstanding Norton associates were convicted in 2013.

Elizabeth Pitcairn, a 55-year-old former HBOS bank worker from Cowdenbeath in Scotland, claims Garner has missed his own deadlines to return her £56,000 pension pot, in a saga that has dragged on for almost a year.

She said: “I think [Garner] has behaved atrociously. How is it in this day and age with all these checks that are in place that he can have my money – basically take my money – and not give it back and there be no penalty to him?”

Further questions are sure to be asked about how Norton reached this point, and how millions of pounds of taxpayer money was staked on the firm.

In July 2015, the then chancellor, George Osborne, said his government’s long-term economic plan was “all about backing successful British brands like Norton”, as he visited the firm’s Leicestershire factory to announce a £4m government grant to Norton and 11 of its supply chain partners.

Four years earlier, the business secretary at the time, Vince Cable, announced a £625,000 government-backed loan by Santander to Norton and said he hoped “that many more companies are inspired by what Norton is going to achieve through this funding”.

Just 13 months ago, Stephen Barclay, the Brexit secretary, also visited the factory. He described Norton as a “great business, great brand”.

The pensions ombudsman says it has received 31 separate complaints about the conduct of the three Norton pension schemes since 2012. It is scheduled to hear a case next month, which has been brought by 30 complainants regarding the conduct of Garner in relation to the schemes.

It has published three determinations directly criticising Garner, who was a trustee of the plans until being replaced by the Pensions Regulator last year.

In May 2019, the ombudsman stated: “We have received a number of complaints concerning the trustee’s failure to action members’ requests to withdraw their monies from the scheme, and from two other pension schemes of which Mr Garner is the sole trustee; the funds of which are also invested in Norton Motorcycle Holdings Limited.”

Apart from the angry pension fund members, Norton customers are also complaining that they have paid deposits for motorcycles, but have no idea when they will receive their bikes.

Tony Smith, a bike enthusiast from Sussex, says he ordered a Norton Dominator Street from the company last August, and paid the full purchase price of £22,000. He says he was informed his bike would be ready in September, November and then December – before being told the firm would be starting work on his bike this month. He has still to receive it.

He said: “I wish I could tell you where my bike is. I’ve had numerous promises of when my bike would be made. My bike was never made and of course now my bike won’t be made. It got to the point where people weren’t returning my calls, my emails weren’t being answered. Emotionally I’ve written the money off. I’m furious.”

Now that the firm has fallen into administration, with accountants BDO appointed on Wednesday to manage its affairs, it looks even more unlikely that this tale will end happily for pension fund holders and customers.

Many of the pension funds of the 228 members that found their way into Norton during 2012 and 2013 were raised by a conman called Simon Colfer.

He was given a suspended prison sentence in 2018 after pleading guilty to duping pension holders into transferring funds into pension schemes, including Norton, by presenting himself under a false name, which concealed a previous conviction, and not disclosing a previous bankruptcy to his clients.

The pension holders – many of whom were financially vulnerable – had been led to believe they would receive a tax-free lump sum for agreeing to the transfer. In fact, the lump sums left them with substantial tax bills, while Colfer was paid significant fees from the retirement pots.

As part of that series of transactions, fees were also paid by the Norton pension plans to a company called T12 Administration, which registered the pension schemes with HMRC and carried out the day-to-day administration.

Two of the directors controlling T12 were Andrew Meeson and Peter Bradley. They were convicted of a separate tax fraud in 2013, when they reclaimed £5m of tax rebates from fictitious pension contributions.

Court documents from that trial state that about £4m of the £5m was then paid out by Meeson and Bradley to friends, family and associates, including a £990,000 loan that went to Norton.

In a statement, Garner said: “I’m devastated at the events over the last 24 hours and personally have lost everything. However, my thoughts are with the Norton team and everyone involved, from customers, suppliers and shareholders at this truly difficult time.

“Without dialogue Metro Bank appointed BDO administrators yesterday. We are now working positively and proactively with BDO to ensure Norton has the best possible chance to find a buyer. It has become increasingly difficult to manufacture in the UK, with a growing tax burden and ongoing uncertainties over Brexit affecting many things like, tariffs, exports and availability of funding.”