When Gyula Remes died on 19 December 2018, across the road from the Houses of Parliament, there was an outcry. Remes, aged 43, was Hungarian and homeless. He had been sleeping in a passage in Westminster tube station that led into Parliament square. It was the second homeless death in the same underpass in 10 months. The Labour MP David Lammy tweeted: “There is something rotten in Westminster when MPs walk past dying homeless people on the way into work.”

Later that day, Remes’ death was discussed in the House of Commons. The Liberal Democrat MP and former health minister Norman Lamb said: “It is grotesque and obscene that we have a homelessness crisis visible just outside the building.” The next day James Brokenshire, then secretary of state for housing, communities and local government, told parliament: “Every death of someone sleeping rough on our streets is one too many. Each is a tragedy, each a life cut short. We have a moral duty to act.” Brokenshire said the government was already acting, with an investment of £1.2bn to reduce and prevent homelessness, and its commitment to halve rough sleeping by 2022 and end it by 2027.

A sum of £5,000 was raised in just two days, in memory of Remes, by an unnamed MP’s staff. Bouquets were bought and impromptu wreaths laid outside Westminster tube. One wreath, cordoned off by a folded black bin liner, featured five bouquets in disposable cups alongside a burning memorial candle. Between the flowers stood a regiment of Stella Artois cans – Remes’ favourite brand of lager. The death of Gyula (pronounced Jeweller) really did feel like a pivotal point.

Q&AWhat is 'The empty doorway' - the Guardian series on people who died homeless?

Show

726 homeless people died in England and Wales in 2018, according to the latest ONS figures. Over the next few months, G2 and Guardian Cities will look behind this statistic to tell the stories of some of those who have died on Britain’s streets. We will tell not just the story of their death, but the story of their life – what they were like as kids, what their dreams were, their hobbies, what people loved about them, what was infuriating. We will also examine what went wrong with their lives, how it impacted on their loved ones, and if anything could have been done differently to prevent their deaths.

As the series develops, we will invite politicians, charities and homelessness organisations to respond to the issues raised. We will also ask readers to offer their own stories and reflections on homelessness. We want the stories we tell to become the fulcrum of a debate about homelessness; to make a difference to a scourge that shames us all.

It is time to stop just passing by.

There was widespread horror that people were dying on the streets of one of the wealthiest boroughs of one of the wealthiest cities in the world. But perhaps there shouldn’t have been. Last November, the homelessness charity Shelter revealed that 320,000 people in Britain were homeless – a 4% year-on-year rise. In 2017, Westminster had more rough sleepers than any borough in the country – 217. The day after Remes died, data was published by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) showing that almost 600 homeless people had died in England and Wales in 2017 – a 24% increase over five years.

Remes’ friend Gabor Kasza talked to the Guardian on the day he died. He said Remes had been given a cigarette by somebody he didn’t know. He inhaled it, convulsed, turned blue and lost consciousness. Kasza was convinced it was the synthetic cannabinoid spice, smoked unwittingly, that had killed Remes.

Kasza and Remes made an unlikely couple. They were different in so many ways. Kasza in his early 20s with perfect English; Remes looking older than his 43 years and struggling to make himself understood with his broken English. Kasza had a girlfriend; Remes was alone. Kasza came to Britain as a nine-year-old with his mother, went to school in London and lived in Tottenham. Remes came in his early 30s, looking for work. Kasza did not drink or take drugs; Remes loved his booze. What they had in common was that they were both from Pécs, the fifth largest city in Hungary, and were homeless.

They met at a day centre for homeless people, the Connection, at St Martin-in-the-Fields, in September 2018. Over four months, until Remes’ death last December, they became inseparable. They looked out for each other, shared food and money, went to the Connection together, returned to their spot by Westminster in the afternoon, and talked up their hopes. Kasza says Remes had simple ambitions. “He wanted a good job, a good house and a big family.” He ended up with none of those.

Six months after Remes’ death, Kasza has moved to Birmingham, where he thought it would be easier to find work. It hasn’t been. He is still jobless and homeless, trying to scrape together enough money to get a roof over his head. And he is still missing his friend. He doesn’t know all the details of Remes’ life – he says homeless people often keep their past, or parts of it, to themselves. But he tells us what he does know.

Kasza believes Remes initially worked as a kitchen porter in London in the mid-00s, but after losing his job he found himself sleeping rough. Remes loved to travel and cook, although there was little opportunity for him to do either on the streets of London. A few years ago, Kasza says, Remes gave up on London and travelled through Europe looking for work. Sometimes he found work, sometimes he didn’t. He was away for about five years, and then suddenly reappeared in Westminster towards the end of last year.

Remes had just returned to the country, was jobless and did not meet the eligibility criteria for benefits, so he found himself back on the streets. In 2014, the then prime minister David Cameron clamped down on what he called “benefits tourists”. As well as having to wait for three months before claiming benefits (which had always been the case), people from the European Economic Area (EEA) looking for work were now only entitled to claim jobseeker’s allowance for a maximum of six months, and then only if they could prove they were actively looking for a job and had realistic prospects of finding one.

Kasza has been homeless, off and on, for the past four years. There have been times when he has been working for the minimum wage and still not been able to afford accommodation. Last year, he lost his job in a warehouse and found himself back on the streets. He and Remes soon became brothers in arms. “He was a very good friend. He’d always help you out if you were in trouble. He’d give you food or money if he had any. He was funny. He made a lot of jokes. He made people happy.”

Life on the streets was monotonous, Kasza says. In the morning they would go to the Connection, which adjoins the famous St Martin-in-the-Fields church in Trafalgar Square, where they could shower and have breakfast. In the afternoon, they would return to their spot by the tube. Sometimes they would go to soup kitchens; other times, they would go job hunting. At night, Kasza would sleep above ground close to Westminster tube station, while Remes would sleep in the underpass a few yards away from a woman called Sarah and her girlfriend. Just before settling down every evening, Kasza would walk down to the tunnel or Remes would come up the stairs to make sure they were safe, and they would wish each other goodnight.

The main thing that kept Remes going was his desire to find a job. He was a proud man, and, unlike Kasza, refused to ask strangers for money. “He would never beg,” says Kasza. “It was work or nothing. He loved working, but it is also hard to find a job if you don’t have any accommodation.” A classic catch-22 – no work, no home; no home, no work.

Kasza says he preferred to work, but often there was none, and anyway he could make more money begging – occasionally as much as £100 a day, and usually £200-£300 a week. That was one of the attractions of Westminster – wealthy people or happy-go-lucky tourists passing by. They may be unlikely to stop and shoot the breeze, but they did sometimes drop a fiver in his cup. Kasza would save whatever he could, and put it in the bank. He hoped to save enough money to move into private rented accommodation.

Occasionally, politicians gave him money. “Ed Miliband spoke to me and gave me his email when he was leader of the Labour party. He gave me £5 and asked me why I was homeless. I said: ‘I’ve been here in the UK a long time – they should give me a house.’ He said he would try to help me.” Did he see him again? “No, that was the last time I saw him.” Miliband was one of the few who did stop. “Most of them don’t know whether we are dead or alive.”

Remes hated the discomfort and indignity of being homeless. “It’s not very nice,” Kasza says. “You sleep on the floor, and it’s dirty. You get drunk people coming out of clubs or going in, making noise. Gyula was a bit scared being on the street. He always wanted to get off. That’s why he was so determined to get a job.”

Kasza says Remes loved to drink if he could afford it – cheap cider or Stella. How much? “Maybe four cans of Stella. Maybe he’d get drunk every second or third night. He was a happy drunk.” Kasza says that, although he never saw Remes out of control, his friend did want to stop drinking. “He would tell me that he was only drinking because life is emotional, and because he wanted a job and felt alone. I would try to persuade him not to drink. One time he stopped for a couple of weeks and then started again.”

Kasza says they got little support from outreach workers. He claims they are not often seen, and, when they are, rarely offer practical support. “They just say there is no room in the shelters or you cannot stay in them because you do not qualify for benefits.”

Another problem is that trust appears to have broken down between homeless people and outreach workers. Today, big homelessness charities bid for contracts from local government. Those that win them are often thought to be beholden to their paymasters. In 2016, the Home Office decided that people sleeping rough in Britain were abusing EEA free-movement rights, and could be removed. In March 2017, it was revealed that big homelessness charities, including St Mungo’s, had been passing information about rough sleepers to the Home Office, leading to their removal from the UK – 127 non-UK-national rough sleepers were deported in a two-month pilot operation in Westminster. But in December 2017, the high court ruled that the Home Office policy to deport rough sleepers from countries in the EEA, known as Operation Adoze, was unlawful.

Not surprisingly, by that point homeless people from the EEA, such as Remes and Kasza, had become suspicious of outreach workers. “I have a few friends who were sleeping rough somewhere near us in Westminster, and they got taken away for sleeping there and held in a detention centre,” Kasza says.

Gyula Remes died on a cold December night. Earlier in the evening, he had complained that life was too tough, and he couldn’t continue in this way. But, as the drink flowed, he began to relax. It was only a week until Christmas, and the atmosphere among the Westminster rough-sleeping community was festive. “A lot of people from my country were sleeping down there. Everybody was drinking and happy,” Kasza says.

He thinks it was about 10pm that he went upstairs to his spot by Caffè Nero. Just before settling down for the night, at around 11pm, he went back down to the underpass to say good night and make sure everybody was OK. Remes was blue in the face, lying on his stomach and choking. His friends said he had been fine until he smoked a bit of a cigarette he had been handed by a young homeless man, and began to convulse. There is no way Remes would have touched it if he had known it had been laced with spice, Kasza says – he didn’t even smoke regular cannabis. “It was definitely spice. We were so sad, shocked, panicking. One of the other guys called the ambulance. We heard the next day he had died. Everybody was crying.”

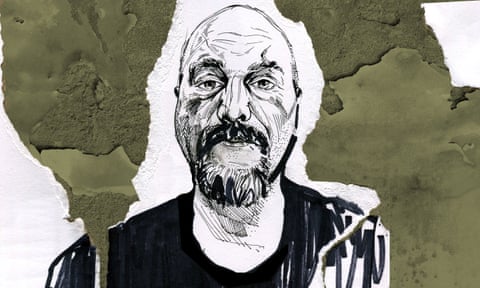

‘He made people happy,’ says Gabor Kasza of his friend Gyula. Photograph: Fabio De Paola/The Guardian

Five months on, how has Remes’ death affected Kasza? “It has made me more sad about people not counting and people not caring. We thought things might change after Gyula’s death, people would start caring, but nothing has changed.” His move to Birmingham has not worked out. He thinks it is even harder for him because there are so few homeless charities in Birmingham to help him.

It all seems so far away from his childhood when he sailed through his GCSEs, did a diploma in animal care and dreamed of becoming a farmer. Five years ago, his mother moved to Amsterdam to live with her partner, and he has struggled with housing ever since. Kasza is not the first in his family to experience homelessness. His father has been homeless in Hungary for much of the past 15 years, even though he works as a builder. This is one of the reasons he would not go back to Hungary. Despite everything, he believes he has better prospects here. More to the point, having spent most of his life here he regards Britain as home – even if it has often felt like an unwelcoming one.

Kasza is remarkably sanguine about the way life has turned out for him. He says he is thankful for his health, his girlfriend and the fact that he still has a future to look forward to. Somehow, he has retained his appetite for life, despite all he has seen. He remains convinced that the next stroke of luck is just round the corner.

In Westminster, Labour MP David Lammy is multitasking – heading towards a meeting while explaining why he reacted so passionately after Remes’ death. He says it was a moment of revelation. “I couldn’t believe how quickly the political class had become indifferent to this suffering. We have people sleeping on Westminster station outside one of the Commons entrances, and 650 MPs have stepped over those people on their way into work. It’s a travesty. In relation to our welfare state, our safety net, our morality really, because in the sixth richest economy in the world it simply should not be the case that so many people are without housing. I tweeted because I felt a sense of despair and loathing for a system that I’m part of.”What worries Lammy is that we have accepted homelessness as the norm. “What we’re seeing now in Britain is a whole community of people who have no stake in society.” Every day on his way to and from work, he passes Stroud Green bridge (next to Finsbury Park tube station in North London), which has become one of London’s contemporary cardboard cities. How does that make him feel? “I feel shame. I feel very upset that my young children, not yet teenagers, are becoming immune to them; immune to people who are sleeping under the bridge.” Does he think anything has changed for the better since Remes’ death? “No! Things have got worse.” Actually, he says, one thing has changed. ”They’ve put up a barrier at Westminster tube to stop homeless people sleeping in the tunnel.” His voice rises in disbelief.

Commuters walk pass Dawn Hodgson the memorial she and others created for Gyula. Photograph: Jack Taylor/Getty images

Westminster is dysfunctional, says Norman Lamb – so many homeless people on the one hand, so many unoccupied buildings on the other. From his office in Portcullis House, next to the Houses of Parliament, he points out a nearby high-rise approved by Boris Johnson during his tenure as mayor. “It’s largely owned by oligarchs, but it’s very rarely occupied … I have argued for a punitive tax on any dwelling in London that is left empty. I can’t understand why nobody has ever done it. It’s the obvious thing that would end the problem or raise substantial amounts of money that you could use to house people.”

Lamb also voices his disgust at the barrier that has been erected in Westminster tunnel. “There’s no doubt a security justification, but the fact is it’s closed off an area where people could get shelter overnight.”

Last week the New Statesman revealed that two months after Remes’ death the chaplain to the Speaker of the House of Commons, Rose Hudson-Wilkin, complained to parliamentary authorities about the “ongoing stench” and “unsanitary state” created by rough sleepers in the underpass.

It is a hot May day, and Southwark coroner’s court is empty except for the two of us, a journalist from a news agency and a handful of staff behind a glass window. The inquest cannot begin at 1pm as scheduled because assistant coroner Philip Barlow is not here yet. It starts at 1.26pm, and is over by 1.52pm – Gyula Remes’ life is done and dusted in 26 minutes. Statements are provided by the head of outreach at St Mungo’s, Kathleen Sims, and Jeremy Bernhaut for the Connection. Neither Sims nor Bernhaut are here in person. It all seems so desultory – a far cry from that December day when Remes died and politicians, campaigners and the media voiced their outrage that a rough sleeper could die on the streets outside parliament.

Barlow tells the court that Remes has no family in Britain, but he believes there is a brother in Canada. There are few concrete facts about Remes’ life. Barlow talks about Remes’ desperation to work – in the short-term as a kitchen porter, with a long-term goal of getting a forklift licence. We also hear that drink sometimes got in the way of the prospect of employment. On 8 October, he was told by a potential employer that he smelled of alcohol, and a week later his caseworker at the Connection also told him he smelled strongly of booze, and should address that before his next job interview. But things were looking up for Remes: he was doing part-time kitchen work and had just been offered a full-time job.

We learn that St Mungo’s and the Connection first had contact with him on the streets in 2006, and worked with him on and off for seven years until he left to live – and work – in Malta, France and Hungary. After five years abroad, he returned to Britain in September 2018 and was spotted back on the streets by St Mungo’s in October 2018.

Remes was offered 12 weeks’ accommodation at the Missionaries of Charity in south London, a hostel run by Catholic nuns with a strict no-alcohol/drugs policy. At the time, it was believed that he was working irregular hours as a street cleaner. On 26 October, he was thrown out after returning home late three nights in a row.

Sims’ statement reveals that St Mungo’s street outreach services team saw him sleeping rough on 30 October in the tunnel at Westminster tube station, but he had refused to give them his details. Barlow says Remes was rejected twice for emergency accommodation at the Connection in October and on 11 December, a week before he died. He was told the hostel was full, but that, even if it had not been, he would not have been allowed in. “He did not meet the criteria for accessing it because he had not started work,” Barlow says. “Also, because his working hours were due to be irregular, he did not meet the criteria.”

This is where the story of Gyula Remes becomes Kafkaesque. The notion that somebody can only meet the criteria for an emergency shelter if they are working seems absurd. Yet this appears to be the case, because working and paying tax is the only way he would have been eligible for benefits. Not only that, he would have to have been working regular hours to qualify for a place. In fact, according to Kasza, he had already started working full-time and had received his first payment the week he died.

The more we examine the last months of Remes’ life, the more he looks like a victim of the government’s hostile environment policy. Here was a man who refused to give his name to the very charity that was supposed to support him (a charity that had been found to be helping the Home Office deport EEA nationals); a man not allowed to claim job seeker’s allowance despite being desperate to find work; a man refused shelter in the December cold because it was believed that he did not yet have a job.

The toxicology report presented at the inquest stated there was no sign of spice or morphine found in Remes’ body, but that he had 369mg of alcohol in 100ml of urine – more than three times the drink-drive limit, according to the coroner. The emergency medical consultant at St Thomas’ hospital said Remes had “mild hypothermia” that was “unlikely to have any clinical significance on a patient’s presentation”. Barlow ruled that the cause of death was cardio-respiratory arrest and acute alcohol toxicity. “My short-form conclusion is that the death is alcohol related,” he said. “But it is impossible to think of the evidence in this case without considering the particular sadness that Mr Remes was hoping to find work and suffered his cardiac arrest in the centre of London near Westminster station shortly before Christmas.”

After giving the cause of death, Barlow said: “It’s no doubt a measure of the pressure the various charities and organisations are under that he didn’t always meet the criteria for accommodation.” The statement, delivered quietly, but with heartfelt conviction, felt like a rebuke. But it was unclear who was being rebuked.

Just after Remes died, the Connection issued a statement. “We are very sad and sorry to hear about the death of Gyula Remes, and would like to extend our condolences to his family and friends. We worked closely with Gyula and will remember him as a funny, charming and amiable man – he always had a smile on his face and was well liked by everyone who worked with him. Just before his death, he told us he was working part-time as a kitchen porter, and working towards getting into full-time employment. We were also helping him to get into a night shelter while he secured a full-time job.” What the statement didn’t say is that the Connection refused him a place at its own night centre the week before he died.

The Connection is one of the country’s best-known homelessness charities. For more than 90 years, BBC Radio has supported St Martin’s work with homeless and vulnerably housed people. Over the past two Christmas appeals, Radio 4 listeners raised more than £5m to help three homeless charities, including the Connection, provide shelter, food and advice. We ask the Connection if any of the staff would like to share their memories of Remes. The press office replies that staff members “are not keen on being interviewed face to face”, but that the chief executive, Pam Orchard, is happy to meet us.

A memorial marks the place where Gyula Remes used to sleep. Photograph: Tom Nicholson/LNP/REX/Shutterstock

On the ground floor at the Connection, homeless people are using computers in a large glass-fronted room. They come to the Connection to shower, have breakfast, reconnect with their home city or country, and find work. We take the lift to the second floor and Orchard’s office. She has worked in the homelessness sector for 15 years, and has been at the Connection for the past two.

She reads out a list of anonymised tributes to Remes from a printed sheet of paper. One staff member remembers that, in 2008, he would always attend the Connection with a close friend, and that they were something of a double act. Orchard says that although she never personally knew Remes, her staff were fond of him. “Gyula was good-natured. He was quite a big guy. Somebody describes him as a gentle giant. He never used his size to intimidate people.” She fast-forwards a decade to 2018 when he returned to London and the Connection. “By now, he was drinking a lot more. He’d be visibly under the influence in a way he hadn’t been in his previous engagements. He said he was drinking because he had time on his hands.” Orchard looks up from her notes. “Often people drink because their mental health isn’t great, and they are self-medicating.”

We ask her what criteria Remes failed to meet for a place in the emergency shelter just before he died. The atmosphere becomes frosty. Orchard asks us to turn our recorder off. We decline to do so, saying this should be a matter of public record. She says the issue of criteria is complex, not one that can be captured in a soundbite or headline.

“We do our absolute best with limited resources,” she says. “If something goes wrong, which it inevitably does, because lots of our clients are extremely vulnerable and have got complex needs, there is a temptation to look for someone to blame and to look at what someone’s engagement in the service has been, and then find reasons to pick holes in what they did in order to demonstrate that if only they could or should have done something it would have been different. So you can look at our night shelter criteria as much as you like, and go: ‘If you’d done such and such, that wouldn’t have happened.’ But it feels a bit like you’re shooting the messenger.”

We ask whether anybody from the Connection attended Remes’ funeral, and whether it held its own service. She says she is unsure, but mentions Marcos Amaral Gourgel, a Portuguese former model who died homeless in Westminster ten months before Remes, and who had also been supported by the Connection. After his death, it was revealed that he had been convicted of child sexual abuse in Portugal, and Orchard says the tabloids were critical of the support the Connection had given him. “So we get blamed for not doing enough, and we get blamed for doing too much. You just can’t win, can you? So we’ll just do what we can as well as we can.”

A few days later, the Connection’s press office sends through the criteria for accessing the night centre: people have to be over 18, have been rough sleeping in Westminster, referred from an approved referral agency (the local authority, police, the NHS or other homeless charities), and they have to be “positively engaging with an agreed action plan that is a realistic and sustainable route off the streets”. The statement continues: “The fact Gyula had no access to welfare meant the best and most sustainable way we could support him was to help him access sufficient employment to pay rent in the private rented sector.”

The statement further explains that, although its most recent work with Remes focused on helping him find work, “unfortunately, this had not translated into a realistic and sustainable route off the streets and so we were unable to accommodate him in our night shelter”. We are left baffled. After all, the assistant coroner said at the inquest that Remes had recently been offered a full-time job, and the condolences issued by the Connection after Remes died stated: “Just before his death he told us he was working part-time as a kitchen porter, and working towards getting into full-time employment.”

It is eight months since Gyula Remes died. In Birmingham, Gabor Kasza says he does not know where his friend is buried or his ashes scattered. Nobody seems to know. We tell him about the inquest verdict, that Remes died of a heart attack and acute alcohol poisoning. He says he cannot believe it. He is still convinced spice did for Remes, and that he had had only about four cans of lager that night. He asks why he wasn’t called to give evidence – after all, he knew Remes well and was trying to resuscitate him as he was dying.

Kasza says he has some good news. “I’ve got a job in a cafe. I’ve been working a few weeks now, almost a month. It’s a big cafe. I’m enjoying it. And I’m renting a room with my girlfriend.” Things are looking up, he says.

On 6 July 2019, the Observer’s home affairs editor, Mark Townsend, reported that the Home Office had “rolled out a remarkably similar scheme” to Operation Adoze, despite the fact that the original scheme was ruled unlawful in December 2017. The story revealed that the Home Office had drawn up a programme called the Rough Sleeping Support Service (RSSS), using homelessness charities to acquire and pass on sensitive personal data that could result in the deportation of non-UK-national rough sleepers.

Emails showed that St Mungo’s attended meetings with the Home Office in which discussions were held about allowing outreach workers to enter a homeless person’s data into the RSSS without their consent, which would breach European privacy laws. The Home Office said the RSSS was set up “to help resolve the immigration status of non-UK nationals sleeping rough, either granting lawful status or providing documentation. This enables individuals to access support or assists them in leaving the UK where appropriate.” St Mungo’s tells us: “We do not share any information about our clients with the Home Office without the client’s full and informed consent. In the case of the Rough Sleeping Support Service, our position has always been that people cannot be referred to the service unless they have first received advice and have also given their consent.”

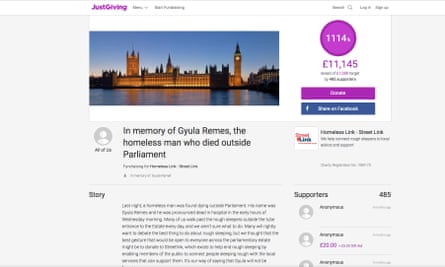

It is early October and the JustGiving fund set up by anonymous parliamentary staff in memory of Remes is still online. Underneath a photograph of the Houses of Parliament at sunset, it says: “In memory of Gyula Remes, the homeless man who died outside parliament.” A badge at the top reveals 485 people have contributed and it has raised £11,145 – the target had been just £1,000. But this seems to be the fund that time forgot. It is open for donations, although nobody has contributed for eight months. As with so much of Remes’ life, indignity is piled upon indignity. Alongside a memorial candle, in smaller type, it says: “In memory of Gyula Remef.”

As for homeless death statistics, they continue to rise relentlessly. On 1 October 2019, the ONS estimated that 726 homeless people died in 2018 in England and Wales, a 22% year on year increase. Westminster council recorded 17 deaths – the highest number among London’s local authorities. Alarmingly, deaths as a result of drug use have more than doubled in the six years the ONS has been recording the data.

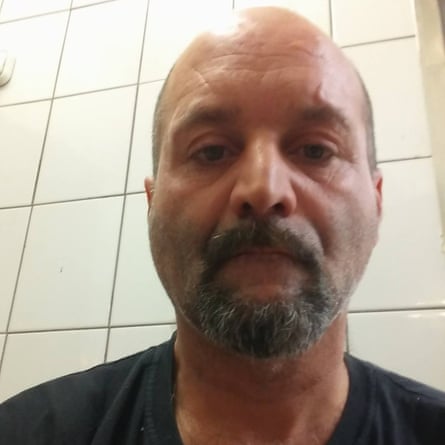

Outside Westminster tube on a warm day, a woman with cropped hair and a toothy smile is sitting in her sleeping bag. We show her a photograph of Remes, and ask if she recognises it. She blinks, then answers. “Who’s that? That’s Julius, innit,” she says. “Of course I recognise him. My girlfriend and I used to sleep near him in the tunnel – just a few yards away.” Sarah Anderson is a 38-year-old Londoner. Like many women living on the streets, she ended up there after escaping an abusive relationship. She says a male former partner stabbed her and claims she lost her right to benefits because she was told she had made herself intentionally homeless.

Anderson holds up the picture of Remes and smiles. “He was lovely – so loving. Every time he walked in, he’d say: ‘You all right, babe? How are you?’ in his fandangled way, trying to speak our language, bless him. He’d always ask how we were, and if we’d eaten.” We tell her that Kasza is in Birmingham, and has a job. Her face lights up. “I know Gabor. How is he?” She says how pleased she is for him and mentions his girlfriend by name.

Anderson talks about the memorial she and her friends made for Remes. “We made it with a black bag all the way round where he used to sleep. We got candles; we even got the politicians involved. They were coming past offering us money. We said: ‘Don’t offer us money, go and buy flowers. And they actually went and bought some.’” Do the MPs still speak to her? “No. They used to before it all happened.” Has she got a message for them? “Help us. Get us off the streets. Do something.”

After Remes’ death, she says the outreach team came round and gave Anderson and her then partner, Dawn, rail tickets to Newcastle, where Dawn comes from. “We ended up spending Christmas there last year.” Why does she think they bought them the tickets? “More than likely to clear the streets around here. I’m not being funny – there was a hell of a lot of publicity the day he died.”

Like Norman Lamb, Anderson talks about all the unoccupied buildings around her, and how they could be turned into giant luxury hostels. She will be sleeping on the street tonight and for the foreseeable future. She says she could probably get emergency shelter, but her mental health isn’t good, and she doesn’t want to be in a dorm surrounded by addicts, temptation and noise. Has anything changed since Remes died? “Yes,” she says. “They have stopped us going into the underpass where we used to sleep at night. They’ve closed it off with shutters.”

Anderson says she was devastated when she heard of her friend’s death. “Of course, I knew somebody could die on the streets, but when it happens literally lying in front of you it doesn’t half shit the life out of you. It really does. Because you don’t expect it to happen to one of your own.” Does she still think of Remes? “Every day,” she says. “Every bloody day.”

In the UK and Ireland, Samaritans can be contacted on 116 123 or by emailingjo@samaritans.org or jo@samaritans.ie. In the US, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline is 1-800-273-8255. In Australia, the crisis support service Lifeline is 13 11 14. Other international suicide helplines can be found atbefrienders.org

If you are worried about becoming homeless, contact the housing department of your local authority to fill in a homeless application. You can use the gov.uk website to find your local council

Follow Guardian Cities on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram to join the discussion, catch up on our best stories or sign up for our weekly newsletter