Can’t Get You Out of My Head: An Emotional History of the Modern World did – sorry – leave me quite emotional. I cannot – sorry, very sorry, again – get it out of my head.

Adam Curtis’s new series of films (released en masse today on BBC iPlayer) are a dazzling, overwhelming experience. The six hour-and-bit long documentaries set out to tell no more and no less than how we got from there to here. “We” being largely the west, both under our own political, industrial and sociocultural steam and as influenced and inextricably linked to China and Russia, “there” being roughly the mid-20th century and “here” being the polarised, tech-crunched, fragile, teetering edifice we call “now”.

In many ways, Can’t Get You Out of My Head is HyperNormalisation Redux: a longer, deeper dive into a lot of the concerns that animated his 2016 film (made available again on iPlayer in the weeks preceding the new release), in his own readily identifiable style. Carefully curated and obliquely but impeccably soundtracked archive footage is attended by a narrative that stops every few minutes to probe further an idea, a moment, a movement or perhaps a figure who habitually flies slightly under the radar of History-with-a-capital-H. Curtis swiftly anatomises the effects of said thing or person, before returning to the main thrust – the warp across which these many many wefts are skilfully woven – so we end up with a full, rich tapestry.

Curtis’s overarching thesis is made clear at the beginning, perhaps to avoid accusations that a documentary-maker, too, can be one of the tricksters and manipulators of reality at which his creation is about to take aim. “The ultimate hidden truth of the world is that it is something we make. And could just as easily make differently – David Graeber 1961-2020” runs the opening caption.

From there we move swiftly yet steadily through the dancehalls of 50s London as the empire crumbles, as an influx of immigrants arrives to what they had been told was their homeland. How the seeds of American paranoia were sown and the conditions under which they sprouted and flourished – the fertile soil of the JFK assassination, the waters of Watergate, the Valium sold as harmless until it became clear it was anything but, the growing domination by China – is laid out. The chance technological solutions to relatively small problems that led to a capacity for mass surveillance and to unimagined power being handed to banks, giving rise – effectively – to a shadow system of government.

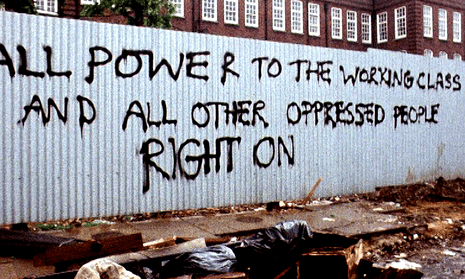

The power dynamic, how it shifts, how it hides and how it is used to shape our world – the world in which we ordinary people must live – is Curtis’s great interest. He ranges from the literal rewriting of history by Chairman Mao’s formidable fourth wife, Jiang Qing, during the Cultural Revolution to the psychologists plumbing the depths of “the self” and trying to impose behaviours on drugged and electro-shocked subjects. He moves from the infiltration of the Black Panthers by undercover officers inciting and facilitating more violence than the movement had ever planned or been able to carry out alone, to the death of paternalism in industry and its replacement by official legislation drafted by those with hidden and vested interests. The idea that we are indeed living, as posited by various figures in the author’s landscape and (we infer from the whole) the author himself, in a world made up of strata of artifice laid down by those more or less malevolently in charge becomes increasingly persuasive.

Whether you are convinced or not by the working hypothesis, Can’t Get You Out of My Head is a rush. It is vanishingly rare to be confronted by work so dense, so widely searching and ambitious in scope, so intelligent and respectful of the audience’s intelligence, too. It is rare, also, to watch a project over which one person has evidently been given complete creative freedom and control without any sense of self-indulgence creeping in. It is always exciting to be in receipt of the product of a single vision. Not quite singular, perhaps: I suspect a lot of men born, like Curtis, in the 1950s, harbour many of the same concerns and would make a lot of the same arguments, although most would lack the ability to enshrine them so accessibly or attractively. But nevertheless, a triumph. For Curtis, of course, but also for publicly funded broadcasting. No commercial channel would have touched this thing. Unless, of course, that’s just what Auntie wants us to think.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion